Build Git helpers from scratch with Bash and fzf

Published

Table of content

fzf is a command-line fuzzy-finder you can run in your terminal to filter any list of files, command history, and more. fzf is versatile and can be used in combination with other tools such as grep and Git.

In this blog post, we’ll explore how to create small bash helpers for Git using fzf.

By the end of this post, you’ll understand what fzf is and how to combine its power with other tools. I hope this tutorial also gives you lots of ideas for applying similar techniques to build your own helpers. Let's get started!

Note: if you're looking for a prebuilt plugin with Git and fzf integrations, check out fzf-git.sh by the creator of fzf. This blog post focuses on building small helpers from scratch combining different programs to make the whole thing less intimidating. Playing around with Bash and fzf is a lot of fun. I hope you enjoy the post!

What fzf is and how to install it

fzf is a command-line fuzzy-finder. It is a tool that enables you to quickly browse any kind of list and search for matches by typing.

In the fzf repository on Github, you can find detailed instructions on how to install it based on your operating system.

On MacOS, the easiest way is to install it using homebrew:

brew install fzfOnce you’ve installed it, if you type fzf in your terminal, you should see a list of all the files in your current directory.

fzfIntegrate fzf with Bash

fzf integrates well with several shells, including Bash and Zsh. Integrating it with your shell activates a series of cool features, such as being able to select a command in your command-line history and paste it.

Add this to your bashrc:

# Set up fzf key bindings and fuzzy completion

eval "$(fzf --bash)"If you are following along using another shell, check out the official documentation on how to set shell integration.

Don’t forget to source your shell config after modifying it (e.g., source ~/.bashrc).

Now, what does adding shell integration do?

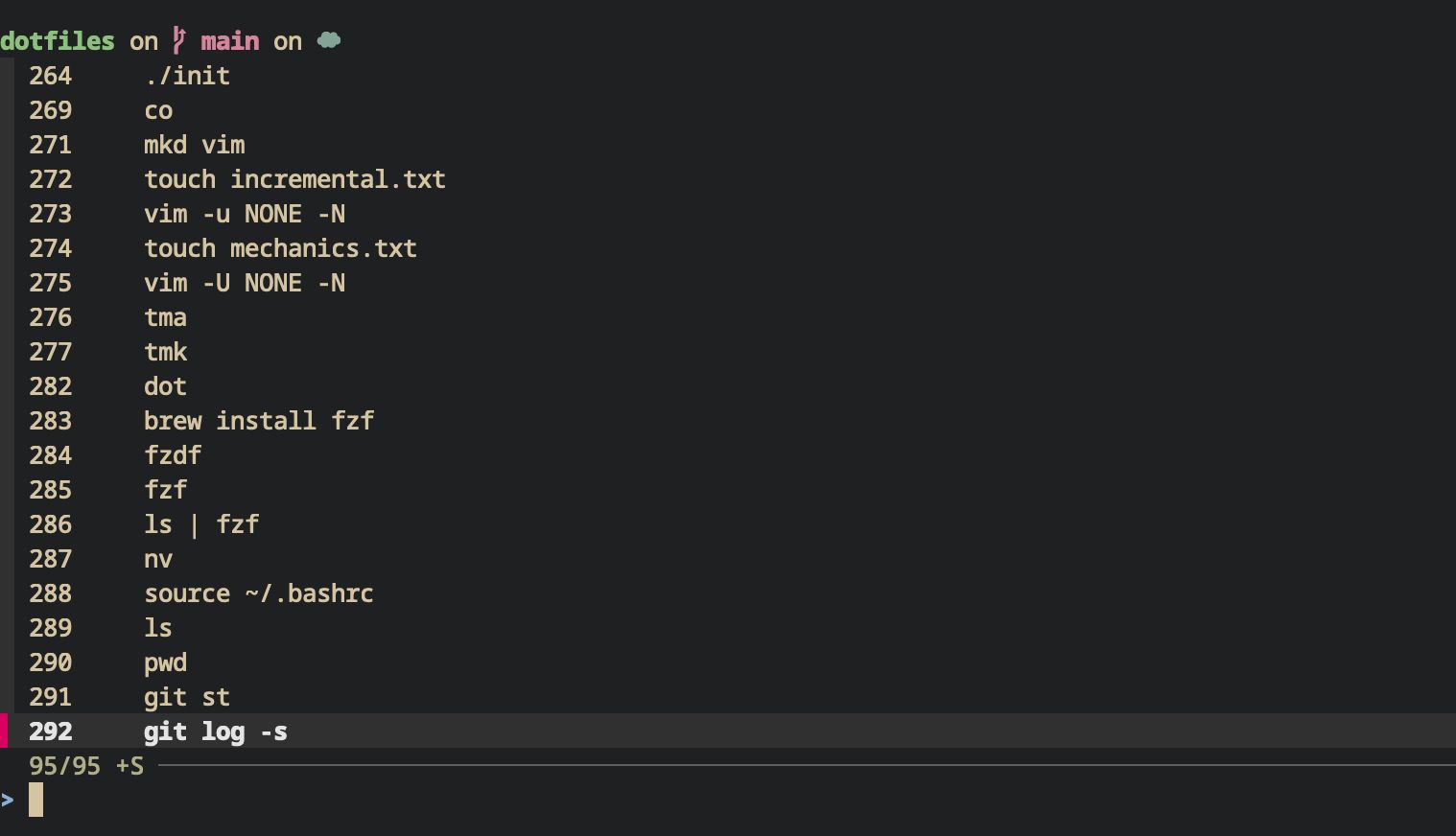

You should now be able to type <Ctrl-r> (Control key + r) in your terminal, select a command from your history, and paste it directly into your terminal.

I use this keybinding all the time. Now, let’s move to the next level and see how we can build useful utilities with fzf.

Combine the power of fzf with Git to create small helpers

fzf is a fuzzy-finder, and you can pipe data from many sources, including Git, into it. This makes it easy to create small helpers. Let’s build a couple of helpers to use Git more efficiently.

To follow along, create a new file in your home directory called .bash_helpers (you can call it whatever you want!):

touch ~/.bash_helpersThen, source it in your .bashrc. Sourcing it tells your shell to import all the functions from the ~/.bash_helpers so you can use them.

# Add this to your ~/.bashrc

source ~/.bash_helpersIt is a good way to keep things more organized.

After modifying

.bashrcor.bash_helpers, don't forget to source your shell config (source ~/.bashrc) in your terminal to apply the changes.

Let’s create a helper to check out a specific git branch

If you navigate to a local Git repository, you can list all of your branches using:

git --no-pager branchIn the above command:

--no-pageris used to remove Git pagination and get the full list of branches.

If we pipe it to fzf, we end up with a list of the git branches that we can search through and select.

git --no-pager branch | fzfThe idea for this first example is to create a helper that shows us the list of branches through fzf and, when we select a branch, we switch to that branch.

In the .bash_helpers, let’s create a function and let’s call it, for instance, sfb (for “switch find branch”):

function sfb() {

local line branch

line=$(git --no-pager branch -vv | fzf)

branch=$(echo "$line" | sed -E 's/^[* ]+([^ ]+).*/\1/')

git switch "$branch"

}Let's break down what this function does:

- With

local, we create two local variables scoped to the function:branchandline. linestores the full row selected from the fzf list, which includes extra info like the tracking status.branchstores the branch name extracted from thelinevariable.- We use

sedto extract the branch name. When you rungit branch, you’ll see output like this: an asterisk in front of your current branch and some extra information like tracking details. Thesedcommand strips away all this extra formatting to get a clean branch name. - Let's look at what this

sedcommandsed -E 's/^[* ]+([^ ]+).*/\1/'does.sedis called a stream editor. It is a way to modify a stream of text.-Eenables us to pass a regular expression to sed to edit a given string.^[* ]+: We start by matching any asterisk or space at the start of the line.([^ ]+): It is a capture group for the branch name. It takes any subsequent character that is not a space. And it will stop the capture group once it encounters a space..*: We match with.*any other character that follows the branch name.- With

\1, we tellsedto replace the input string with the capture group that contains the branch name.

git switchis equivalent togit checkoutand will check out the branch we selected.

Next, before testing it, we could add an extra check to make sure the command is run in a Git repository. Let's use the handy command git rev-parse --is-inside-work-tree. This Git command returns a boolean indicating whether we are in a Git repository or not.

function sfb() {

if ! git rev-parse --is-inside-work-tree &>/dev/null; then

echo "Error: Not inside a Git repository"

return 1

fi

local line branch

line=$(git --no-pager branch -vv | fzf)

branch=$(echo "$line" | sed -E 's/^[* ]+([^ ]+).*/\1/')

git switch "$branch"

}git rev-parsereturns a boolean. If it returnsfalse, we exit the function.&>/dev/null: It is a way to ignore the output of the Git command.&>redirects both standard output and standard error to/dev/null, which is what is called a "Null device". It is a way to discard the command output completely.

Let’s give it a go. Save your file and go back to your shell. Source your bashrc (source ~/.bashrc). Go to a local repository that has several branches and type in your command line:

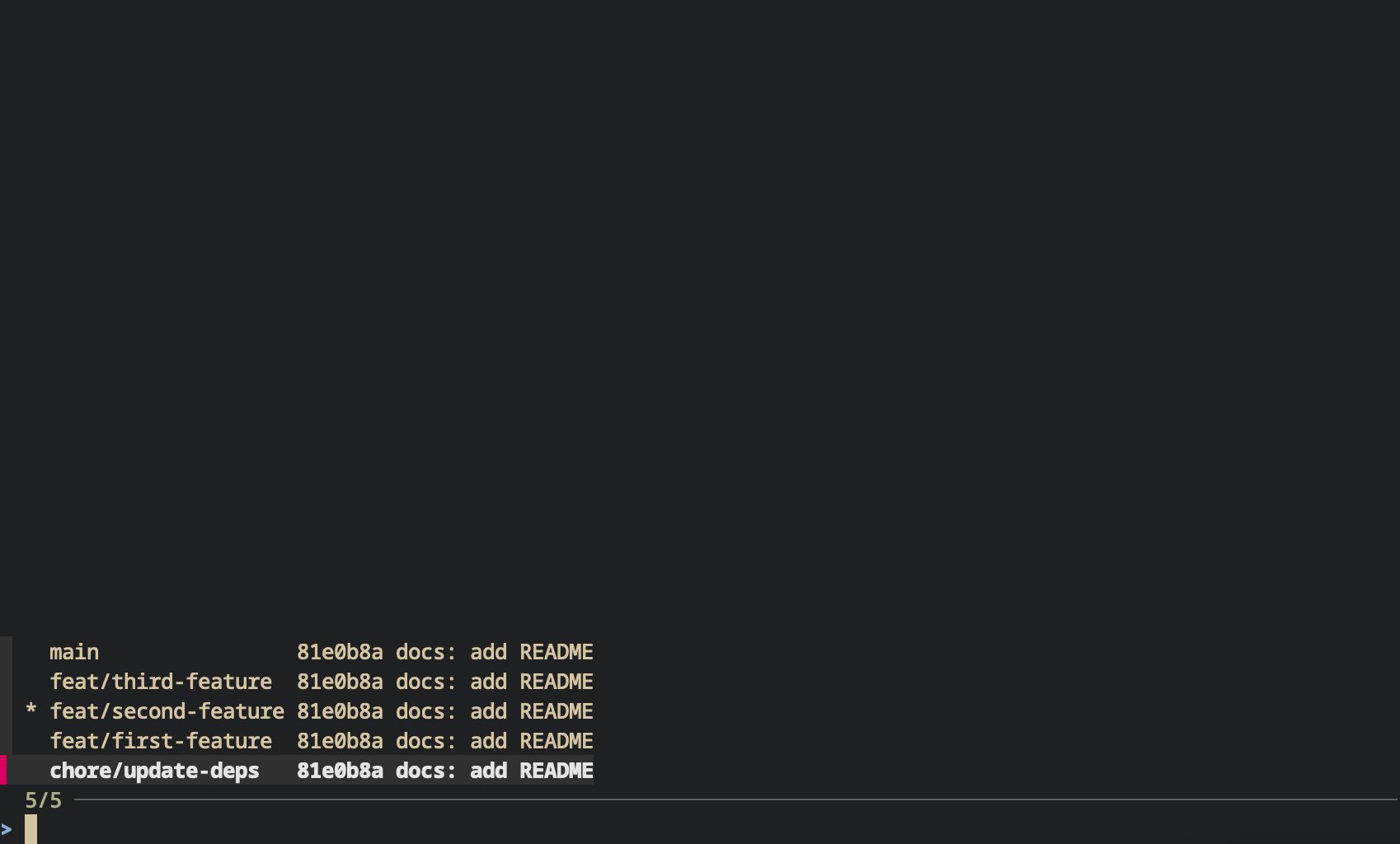

sfbHere's an example output of running this command:

You should see the fzf picker showing all your Git branches. The * in front of the branch indicates your current checked-out branch. If you select one, you should now be checked out on that other branch.

Extracting the git rev-parse check in its own function

We will reuse the logic to check whether the directory is a Git repository. Let's extract the logic with git rev-parse in a function for easier reuse. In your .bash_helpers, add:

function ensure_git_repo() {

if ! git rev-parse --is-inside-work-tree &>/dev/null; then

echo "Error: Not inside a Git repository"

return 1

fi

}We can then use it in our sfb helper:

function sfb() {

ensure_git_repo || return 1

local line branch

line=$(git --no-pager branch -vv | fzf)

branch=$(echo "$line" | sed -E 's/^[* ]+([^ ]+).*/\1/')

git switch "$branch"

}ensure_git_repo || return 1 is a shorthand syntax. It is equivalent to doing:

if ! ensure_git_repo; then

return 1;

fiWith the || syntax, if the first expression is truthy, the second expression does not get checked. In our case, if ensure_git_repo is successful (returns 0), the return 1 won't get evaluated.

Let's create a helper to delete a Git branch using fzf

Using a very similar logic, we can create a helper to delete a branch.

Let’s create another function dfb (that stands for “delete find branch”) and reuse the branch selection through fzf logic:

function dfb() {

# Let's use our helper to check if it is a Git repository

ensure_git_repo || return 1

local line branch

line=$(git --no-pager branch -vv | fzf)

branch=$(echo "$line" | sed -E 's/^[* ]+([^ ]+).*/\1/')

}Now, because it is a destructive operation, let’s add a confirmation step. With Bash, we can use read -p to get user input and confirm that the user wants to delete the branch:

function dfb() {

ensure_git_repo || return 1

local line branch

line=$(git --no-pager branch -vv | fzf)

branch=$(echo "$line" | sed -E 's/^[* ]+([^ ]+).*/\1/')

# show the user what command it is about to run

echo "git branch -D $branch"

read -p "Are you sure you want to delete this branch? [y|n]" -n 1

echo ""

if [[ $REPLY =~ ^[Yy]$ ]]; then

git branch -D "$branch"

else

echo "Branch deletion aborted"

fi

}read -pwill prompt the user.-n 1means we only take one character from the user input.$REPLYis a global shell variable. By default,readwill store the user input in$REPLY- In the

ifstatement, we use=~to match the user input with a regular expression^[Yy]$. If the user typesYory, we delete the branch.

Let’s try it out. In your shell, source your bashrc and then type:

dfbIt should show you a list of branches. If you select one, you will be prompted to confirm whether you want to delete it.

![Shows the output of running the function in the terminal. Once a branch to delete is selected, it shows a confirmation prompt that says, "Are you sure you want to delete this branch? [y|n]"](/blog/build-git-helpers-bash-fzf/lPG56UvqqB-1018.jpeg)

Let’s create a helper to choose a commit to rebase a branch onto

One of my favorite Git + fzf utilities is one I call gri. It enables me to choose the commit I want to rebase my branch on. Let’s build this one together.

First, let’s create a Bash function called gri (it stands for “git rebase interactive”).

function gri() {

ensure_git_repo || return 1

}First, we need to list all the commits and pipe them to fzf.

git log --color=always --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit--color=alwayskeeps the colored output.--pretty=onelinekeeps the commit information on a single line.--abbrev-commitshortens the commit hash.

If you try out this command, it will print out in this format:

Next, we need to pipe it into fzf to allow the user to select a commit.

function gri() {

ensure_git_repo || return 1

local line commit

line=$(git log --color=always --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit | fzf --ansi)

}To keep the colored output, we pass --ansi to fzf.

To extract just the commit hash, we can use sed again. Here’s what the final function looks like:

function gri() {

ensure_git_repo || return 1

local line commit

line=$(git log --color=always --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit | fzf --ansi)

if [[ -z "$line" ]]; then

return

fi

commit=$(echo "$line" | sed -E "s/^([^ ]+).*/\1/")

git rebase "$commit"

}- We use a capture group in the regular expression in

sedto capture the commit hash only. -zis a string test operator in Bash. It checks if the string is empty. This condition handles the case when the user doesn’t select a commit.

Now test it in your terminal:

griYou should see a menu with your commits. If you select one, you’ll be taken to Git’s interactive rebase menu.

Other ideas

In this post, we explored the power of fzf, taking git as an example. But you can use it with many other programs. One recent use case I had was that I wanted to select a Docker container to execute a command inside of it. At work, I have at times 60 containers running simultaneously, so it can be tricky to find the one I’m looking for.

I ended up doing a command that looked like that:

docker exec -it $(docker ps --format "{{.Names}}" | fzf) sh

docker container execallows you to execute a command inside a running container.-itmeans that I want to have an interactive mode within the container.shis the program I want to launch within the container.docker ps --format “{{.Names}}”lists out only the names of the containers.

We could put this command in a Bash function, too. There are so many useful use cases of using fzf. The sky is really the limit!

Complete code from this post

You can find all the code from this post in the fzf-git-tutorial repository on Github.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we explored fzf and built together a couple of Bash utils combining the power of fzf with Git. We built one to check out a Git branch, being able to pick from the available local branches. We also looked at how to build a helper to rebase onto a commit by using fzf to see a list of the different commits. We've only really scratched the surface of all the useful things we could do with fzf. I hope this blog post gives you some ideas! You can find all the code examples from this tutorial in the fzf-git-tutorial repository. Like always, if you have any questions or would like to share some of your own utils, don’t hesitate to reach out on Bluesky!

Versions used in this post

Here are the versions of Bash and fzf used in this post:

bash --version

# GNU bash, version 5.2.37(1)-release (aarch64-apple-darwin23.4.0)

fzf --version

# 0.65.0

git --version

# git version 2.50.0You don't need these exact versions, but if you run into any issues (particularly with Bash), try updating Bash or fzf.

Further resources

- fzf Github repository

- Bash scripting cheatsheet

- fzf-git-tutorial repository

- My Bash utility functions in my dotfiles

- For a more advanced Git + fzf integration, check out fzf-git by the creator of fzf